Bad King John, Northamptonshire and Magna Carta

Posted 3rd April 2024

This month Laura Malpas explores King John’s impact on the county of Northamptonshire during his tempestuous reign

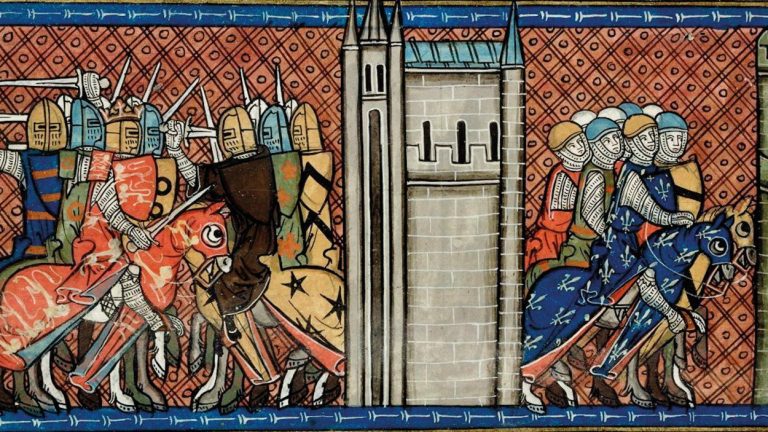

Many of us are familiar with the story of bad King John being forced to sign the Magna Carta by angry barons at Runnymede. There’s even a monument there celebrating the event. Less well known is that this significant document was composed and written in our own county of Northamptonshire. Here’s the story of how King John’s behaviour compelled the English barons to codify the law.

It was a complete surprise to all that John, the youngest son of Henry II, became king. He had four older brothers, including the dashing Richard the Lionheart, and was never expected to reign. He was never trained in kingship and instead of a royal Christian name, was given the nickname John Lackland as he was not expected to inherit significant territory.

His father prepared him for life as a scholar placing him under the direction of legal expert Ranulf de Glanville. Glanville penned a treatise on English law, noting that it was largely unwritten, and that it was uncertain if a monarch could nonetheless be made to obey it. The idea that rules might be made to be broken was clearly a lesson noted by young John.

John’s reputation was sullied by the Victorians who loved to paint historical characters in terms of heroes or villains, but modern historians assure us that he was a thoroughly unpleasant man. Cruel even for the times, and especially so when the odds were in his favour. However, his cowardice in the face of a powerful enemy was well known and his poor military leadership earned him another nickname, John Softsword. Contemporary complaints about John included blackmail, extortion, murder, and exploitation of women.

These complaints were often ignored by his indulgent family. His self-serving treachery led to him attempting to steal the crown from his brother Richard whilst he was away crusading. Richard foolishly forgave him, describing him as ‘a mere boy’ even though he was nearly thirty.

John’s greatest triumph was to outlive his brothers. Henry II anticipated that his heir was to be his second son, Henry the Young King, but Henry died prematurely. Richard outlived his next brother Geoffrey and inherited his father’s throne. In 1199 Richard died childless leaving John to take the throne, to the general dismay of the English people.

In 1200, King John gave Northampton a new charter. The town was a centre of political and economic significance at this time. Northampton had the right to hold great royal fairs, where horses, grains and textiles were traded, and records show the King regularly acquiring goods. King John visited the town many times staying at Northampton Castle, where he paid for its maintenance and likely authorised the building of the round tower. In 1207, concerned about its safety in an unstable London, John moved the Royal treasury to the town.

Many interesting snippets in the records show the King’s impact in the town. The royal accounts detail that King John required the constable of Northampton to employ Peter the Saracen and his wife to make crossbows. It is thought that this is the first mention of Muslims in England, and their high wages indicate they were respected tradespeople. Another report from 1205 describes how John raised an army to reclaim lands lost in France, mustering 30,000 men at Northampton, the largest ever raised. Another delightful detail found in John’s household accounts suggests that in 1209, two of the King’s annual twelve baths were taken in Northampton.

From 1205, John was in dispute with the powerful English Church. The king argued with the Pope over control of the wealth, policies, and appointments of senior churchmen in his land, leading to the Papal threat of excommunication. The King’s intransigence led to the realisation of this threat in 1211 when the Pope sent his envoys to meet the King at Northampton. In the Great Hall of the Castle, the Pope’s legate excommunicated the King and gave permission to all his subjects to freely break their oaths of loyalty and instead join with the Pope’s armies. John was outraged, and immediately called up all prisoners held in the castle and began their punishments in front of the throng, blinding, severing hands and feet, and hanging men. When a priest was judged guilty and ordered to be hanged the Papal legate threated to excommunicate anyone who even touched the priest.

The angry Pope asked the King of France to lead an army to invade England and take the Crown on his behalf. French King Phillippe enthusiastically began preparations. This threat alarmed John who was compelled to backtrack and reopen negotiations with the Pope, eventually submitting to him. But the insult from France was not forgiven, and John summoned his Barons and set out to invade France.

Relations with his Barons had deteriorated, especially with those in the North and East of England. Continuous demands for money, campaigning, and cruel punishments to those who disobeyed meant they refused the order to join the King in the invasion. John was forced to return home, humiliated and furious. He raced up to Northampton with an army of mercenaries to punish the rebellious barons, where he was intercepted by Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton. It took the threat of excommunication for the whole army before King John agreed to grant the barons a fair trial. Eventually excommunication was lifted from both the king and his forces.

But King John’s rule of law was far from fair, and more like coercive extortion. Tolls and fines were imposed relentlessly,

rivers were blocked, possessions seized, and people imprisoned on a whim with no redress.

The King’s favourites took advantage and imposed taxes, and any who complained would lose their lands and possessions and face exile. It is easy to see how the legend of Robin Hood arose in connection with this harsh treatment. The only people who could resist this behaviour were the powerful rebelling barons who in January 1215 demanded change. John was forced into negotiations, but it would be on his terms.

John chose Northampton as the place for the confrontation. Whilst hunting at Silverstone, John prepared the scene by installing William Thilly as mayor of Northampton, creating one of the earliest mayoralties in England. He ordered that twelve men ‘discreet and better of the town’ should be appointed to support the mayor, and by extension himself. John formed a new papal alliance, and was given permission to form an army under the pretence of crusading.

The Barons were aware of John’s army, now with the Pope’s protection. Five Earls, forty Barons with their retainers, an estimated two thousand knights plus countless foot soldiers and supporters grouped in advance at the Stamford tournament field near Collyweston before marching to the agreed meeting place in Northampton. Pitching at Northampton’s tournament ground, the Barons realised the King was absent, so they moved on to Brackley’s tournament ground further south in the county. The King stayed away but sent an envoy including Archbishop Stephen Langton to find out what the Barons were demanding. A long list of demands was created, mostly covering what had previously been accepted but unwritten – laws, customs, and practice. It was this list which evolved into Magna Carta, the Great Charter. This list, created in Brackley in 1215, became the basis for all the great charters which followed.

In early May, the envoy returned to King John, now in Wiltshire. He exploded with anger and raged at the list, swearing he would never agree to these demands which would make him ‘no more than a slave’. He sent his denial to the Barons waiting in Brackley. They renounced their oaths of loyalty to the King and declared themselves now to be ‘the Army of God’. They marched back to Northampton and laid siege to the Castle, the King’s stronghold. They failed as they had not brought siege equipment, and moved on to Bedford more successfully.

Many frustrated townsfolk of Northampton raised up and attacked the Castle, killing several of the garrison there. Retribution followed swiftly as the soldiers poured into the town, setting fire to houses and killing the perpetrators.

The Army of God then took Lincoln and London, rapidly gaining supporters as they campaigned. King John capitulated, now fearing for his throne, and reluctantly agreed to sign and seal the Great Charter at Runnymede on the 15th of June.

The Barons celebrated, but all was not won. King John immediately asked the Pope to nullify the agreement and he obliged, declaring Magna Carta ‘null and void of all validity forever’. However, history shows its impact and longevity, as three laws are still present in the both the UK and USA – almost verbatim.

This renunciation of his word to adopt Magna Carta led to another war with the Barons, in which the King burned out Oundle amongst other places. However, John only lasted a further year before dying of dysentery. A contemporary noted at the time ‘Hell itself is made fouler by the presence of John’. To this day he remains the only ‘King John’ in English history as no monarch has wanted their heir to bring ‘Bad King John’ to mind.

To learn more about the story of Northamptonshire and its relationship with the King and Magna Carta, I heartily recommend reading ‘Northampton’ by local historian Mike Ingram ISBN 9798579592910.

The Northamptonshire Heritage Forum has something for everyone interested in learning more about our county’s history. If you would like more information, or are interested in joining the Forum and supporting its work, please visit www.northamptonshireheritageforum.co.uk